To continue the Saturday Evening Post article written by Pete Martin.

I hope I don’t confuse you with the different fonts and colors. I put the part the PR Department provided Mr. Martin in this regular print. The part that Mr. Martin wrote himself in italics, the part that Dad is quoted as saying in BOLD and my comments in blue print.

I recognized Iverson’s Ranch when I arrived in the high, cool hills within an easy auto ride of Hollywood. I had been there a hundred times before. Only I had made those trips sitting in the dusk of innumerable movie houses, this was the first time I had really been there. Hundreds of movies have been shot there since 1914 when the Iverson’s first got the idea of hiring their place out as a ready-made background for motion pictures. Last year they rented their ranch for the making of seventy movies. Sometimes two companies work there at once. But most of the films made at Iverson’s are “shootin’ gallery” ones. Nature has done a favor for the Iverson’s that most ranchers would regard as a catastrophe. She has grown a fine, healthy crop of rocks for them–some as big as houses. There are rocks with caves gouged out of them, rocks that dwarf a posse as it goes pounding past, its breath hot on the necks of a band of rustlers. The movie companies sign an agreement with the owners of the ranch to the effect that, if the Iverson’s so desire, any structures erected for a film must remain when the filming is over. As a result, the place is literally sprinkled with corrals, log cabins and whole Western cowtowns with Silver Dollar saloons, Last Chance cafes, barbershops and general stores, all of them backless and open to the breeze.

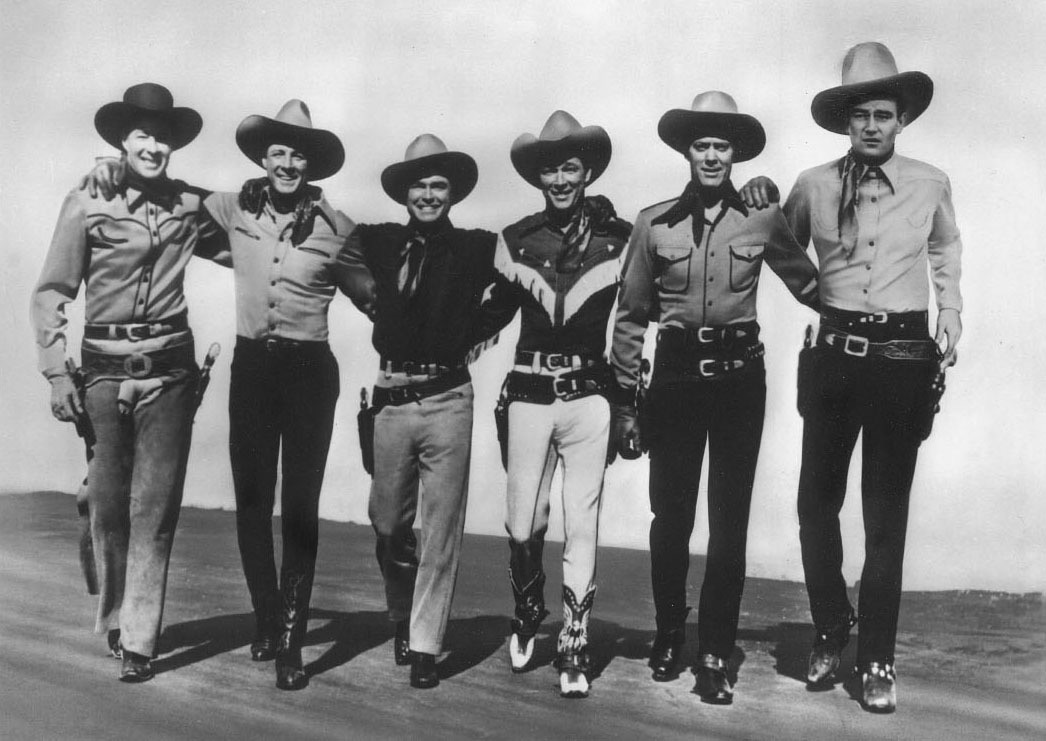

I walked past a group in shirts piped with yellow, baby blue, red and white. Their owners were pleading with a pair of dice which they were tossing upon a blanket. Looking at them, I realized that there was something my tutor in Western movies hadn’t told me. Obviously, in order to be in Western pictures, it was necessary to have hips slim as a snake’s. Cowboy hats, shirts and boots that cost fifty dollars; trousers a hundred and fifty a pair. But even the most expensive pair of trousers can’t make a movie cowboy of you if your rear-end is built along the generous lines of a sofa pillow. Even Gabby Hayes, the bearded, sixty-year-old character actor who appears in all of Rogers’ pictures, has hips an Olympic track star would envy.

I found the lunch wagon and introduced myself to the director, who offered to find Roy for me. I had been warned that, though Rogers was pleasant company, he didn’t like to talk about himself. Presently, the director came back. Beside him was a trim, medium-sized cowboy wearing tightly fitting, superbly tailored, pin-striped trousers. His hips were so narrow that , in comparison, his shoulders seemed startlingly broad. He shook hands and said, “How’s for some breakfast?” “What did you have?” I asked. He looked at me quizzically, “I had an onion sandwich and some Java,” he said. I drew a deep breath and said, “Make mine the same.” When I got it, the sandwich seemed all onion and a couple of yards wide. Tears spurted from my eyes. Watching me eat, Roy had another one. Together, we stood munching. He swallowed and said, “Well, it’s a lot better than hawk, anyhow.” I asked him, “What about hawk?” And he told me about it.

As he talked, I forgot he wasn’t supposed to be easy to talk to about himself. I didn’t remember it until I was leaving. Then I made a mental note always to eat an onion sandwich with a cowboy star. Its potent juices seem to loosen their tongues. There was quite a lot leading up to the “hawk” part of Roy’s story.

He was born in 1912 (actually he was born in 1911) in Cincinnati. When Roy was seven, his parents moved to an Ohio community called Duck Run. “My father worked in a shoe factory in Portsmouth, thirteen miles away, but I didn’t wear any shoes at all until I was about grown,” Roy said. “The bottoms of my feet were like elephant hide.” The first horse Roy ever rode was a plow horse, but his youthful movie idol was Tom Mix, which fixation helped him beat down a prosaic adolescent desire to be a dentist. He purchased a second-hand guitar–he calls it a “gittah”–from a pawnshop and learned to play it with the help of a correspondence course. (My Gramps and all of Dad’s three sisters played the Mandolin. Dad, and all three of his sisters, had played a mandolin since they were little kids. Don’t think Dad ever took a correspondence course, ever. But, sometimes he would go along with the PR department too. )

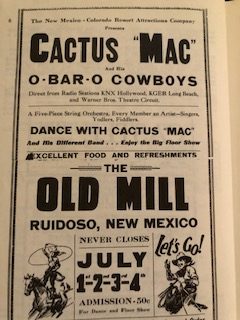

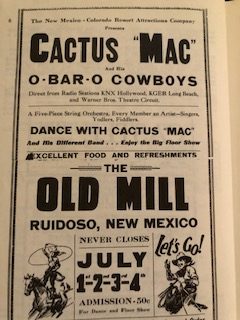

In 1929 he was able to sell an elderly relative (actually it was his father and he was not elderly, just out of work due to the Depression) on the notion that a man past his prime would need help in driving west. After picking peaches near Tulare, California, in the “Grapes of Wrath” belt and spending time spurring a gravel truck over highways, he helped organize a cowboy band called The International Cowboys. They weren’t cowboys and they weren’t internationals, and the singing cowboy business was some-what spavined and bogged to the hocks at the time. No whit discouraged, Roy helped organize another band called The Rocky Mountaineers (Those of you who have read my books, know that The Rocky Mountaineers was actually the first band that Dad worked with and they were already a band before he joined them. Then he joined Benny Nawahi and His International Cowboys. Dad left that group and a new one was formed “Cactus “Mac” and the O-Bar-O Cowboys that featured Dad [Leonard Slye], Tim Spencer and a couple of other musicians) and, when an agent arranged bookings for them through Arizona and New Mexico (they were booked all the way to Texas), they accepted without looking into the project too closely. “What about this “hawk” business?” I asked.“I’m coming to it,” he said.

“We took took off in a beat-up old jalopy, and the famine set in,” Rogers said. Everything except musical instruments was pawned to buy gas and get blowout patches. (Things were soooo bad that Cactus Mac left the group in Hollbrook, AZ, shortly after they set out.) Mostly the group lived sketchily on the pies and cakes which they told their audiences wistfully that they would trade “request numbers” for. “We rode around various towns in the jalopy, hollerin’ out the good news of our arrival to the population through megaphones,” Roy remembered. “But we still weren’t able to lay up a dime. I borrowed a rifle and shells and killed a couple of cottontails. There was a hawk on a telephone wire a hundred and fifty yards away. I had one bullet left. I allowed two feet for the drop and drilled it. When we cooked it, it was so tough we couldn’t get the fork into the gravy. That’s what I mean when I said an onion sandwich is better than hawk.”

The four “cowboys” arrived in Roswell, New Mexico with fifty cents in their Levis and no further bookings in sight (the bookings were there, they just had no money for gas). Roy went to the manager of the local radio station and made a deal for the group to exchange songs for their auto-court bill. But that didn’t solve their food problem, and they continued to remember their fondness for homemade food–especially pies–over the air. One day a pretty, brown-eyed girl drove up, carrying two whole lemon pies covered with meringue inches thick (Dad later married that brown-eyed girl). After the Roswell experience the group broke up and returned to Los Angeles. (They actually continued on to Texas, where Tim met his future wife, Velma.) Rogers then spent a year on a ranch in Montana, where he learned at first hand the things he had been singing about–branding, roping, roundups. He must have given the job intensive study for Yakima Canut, dean of rodeo prize winning bronco busters, said that Roy can ride with any man he ever saw in a saddle, and shoot with marksmen anywhere. There was a period of being a guide for tourists vacationing at the Grand Canyon, doubling in the evening as an entertainer for the guests at the lodges). (I put that last bit in a different color because Dad never did any of it!!! This was completely made-up by the studio’s PR Department!)

When he had saved enough for a few weeks’ coffee and cakes, he went back to Los Angeles to ride the radio ranges once more. Meeting a few pals, he formed a cowboy band known as the Sons of the Pioneers, which now appears in all his pictures. They made a recording of “The Last Roundup” which blitzed the disk market, and they were “in.” As Rogers was telling me this, an assistant director came around the corner of the lunch wagon and told Roy he was needed to make a scene. “I’ll tell you more about it when I come back,” he promised as he started away. I walked over to one of the taller rocks, that looked like a giant egg set on end, and watched Roy ride up to the camera with a party of fellow vigilantes, while a buzzer squeaked for quiet. It was the first time I had seen Trigger. His mane and tail were cream-colored and he had four white stockings. His skin rippled in the sun while the light caught and twinkled in the silver trimmings of his saddle and bridle. Roy and the others on horseback looked knowingly at footprints in the muddy edges of a stream, then spurred past the camera.

When the action had been shot twice more from different angles, Roy came back and took up where he had left off. “I was getting my ten-gallon hat cleaned in Glendale one day when a guy came in and told the proprietor, ‘I got to have a screen test tomorrow at Republic, and I need my hat cleaned quick.’ When I overheard this I snatched my guitar and beat it over to the Republic lot. I tried all morning but I couldn’t get past the front door. Finally, at noontime, some people went in and I pretended I was with them. Inside I ran into a friend named Sol Siegel. I told him why I was there. ‘Have you got your guitar with you?’ Sol asked me. It was outside in my car. I ran all the way to the car and all the way back. Then I sang “My Little Lady” and “Tumbling Tumbleweeds.” I’ve been with Republic ever since.”

Look for Part 3 next week.

Test post

testing description